- Home

- Elizabeth Guizzetti

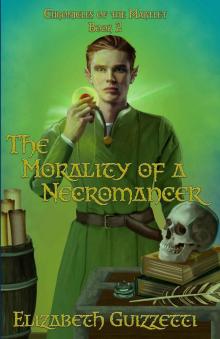

The Morality of A Necromancer Page 9

The Morality of A Necromancer Read online

Page 9

“Learn from your shame.”

*

Village of Macotir

Through the thinned trees along the river, Alana spotted a billow of smoke showing the location of the village of Macotir.

As they drew closer, they could hear working. Axes chopping wood. A plow breaking ground, and the swears of a farmer pulling up roots. Above it, all was the constant ping of the blacksmith’s hammer moving metal.

“Look, someone’s there!” One of the men’s voices called neared the wagon, his words choked with tears.

A hastily-built stone wall surrounded several huts which bore scorched scars. Three old men sat in front of the gate.

“Who goes there?” One asked, holding his ax high in the air.

“Don’t be a fool. Are you blind? Look, it’s Balrea and Balhan and Caraine!” One cried.

“How did you escape?”

The three elderly men crowded around the wagon. The sound of work stopped in the village and men and women rushed forward.

Caraine called out for her mother, but her voice was drowned by questions and embracing arms.

Alana caught a look of panic on the child’s face as she tried to back away from the grasping hands and kissing mouths. Her shoulder’s sagged; Alana grabbed her before she collapsed.

“Eohan!” A large man roared as he hurried towards the gate. Tears streaming down his face. “Eohan! Has my son returned?”

Keeping Caraine under her arm, Alana put her hand out. “No, but I bring word if you would call him your son, Gouren Smith. Where is Fol Baker? I have news that concerns him as well.”

Smith’s eyes opened wide, his cheeks flushed, and he stepped back. “You are the Martlet of House Sildeir?”

Though she wasn’t entirely sympathetic with a man who denied his son’s existence, she felt a twinge of Eohan’s bitterness. “No, that would be Lady Byronia yonder. I am Lady Alana of House Eyreid, I asked: where is Fol Baker?” yound

Smith winced and wrung his hands. “Fol is not here. He went to beg for help at the Great House. I ought to have gone with him. Every night I am haunted. Milady, please, what word do you have of my son, his mother, and brother?” So the man had realized his foolishness.

“To ease your heart,” Alana said. “Aedell died on the slave ship, but Eohan brought honor to his mother’s memory by helping us rescue all the surviving women and children. Though born a butcher, his deeds are worthy of a nobleborn. I’m proud to call him my apprentice. He and Kian are with my nephew Roark.”

Tears swam in Smith’s eyes.

“Caraine is ill.” Alana said, “We need rest, our horses need to be fed and watered if you please.”

“Come, I have little, but it’s yours.”

Alana followed the smith to his shop. Grime over the bellows. Cobwebs lined the corners, but the shared heat from the forge kept it warm.

“Take a seat, milady. Caraine, if you need rest, you can sleep there.” He gestured towards a large hay pallet on the far side of the room.

“Now we’re away from everyone, I’m better,” the girl said, still hanging onto Alana’s hand.

“Well, your color is still pale,” Alana said. “If you don’t wish to rest, sit quietly.”

Caraine cuddled beside Alana on the bench. Eventually, she laid under her arm and rested her head on her lap.

Smith quickly chopped more carrots and threw them in his throws his pottage which bubbled on the fire.

“You’re kind to her,” he said. He did not say for a nobleborn, but Alana heard it in his rebuking tone.

“I learned her mother is the Wisewoman Ylsabet.”

“Aye.”

“And she is in Eyredeir.”

“I used to have a young boy, name of Iav around, but he was carried off, too.”

“If he survived, Byronia and I will find him. We seek the children who were sold before Roark, and I could save them.”

Smith pressed his lips together. “Caraine was … sold … that’s why you’ve been gone so long. And why she looks sickly, while some of the others are strong …” Smith paused, “Milady, what do you apprentice my boy in? As a commoner, it’s not like he can be a Martlet.”

“I’m apprenticing both of Aedell’s sons in War Ending. I am also a Guild War Ender as House Eyreid is not so large that its Martlets don’t need a job to pay the bills.”

Smith’s eyes darted around. “In truth, milady? You wander?”

“For the good of our people,” Alana answered.

“Why haven’t we ever seen you or any other Martlet?”

“Because in any generation there are only fourteen active Fairsinge Martlets and thirteen Daosith Martlets. In order to help those in need, we chase the ruin. I came because ruin came to your village and Lady Byronia needed my help to find who was lost.”

“If you find Iav. Tell him I am alive, and he was a good apprentice, and he can come here to me if he wishes ... Or, by your word as a noblewoman, will you find him a good apprenticeship if he wishes to stay there?”

“By my word, if he is alive, he will have a vocation -- and he will not live as a slave.”

“Good.” Smith looked down at his massive hands. “I know I wasn’t a father to Eohan. Even when he wanted me to be. When you see him again, you tell him, that I am sorry.”

Alana said she would. But it was too late. Eohan would never be Gouren Smith’s son.

*

Chapter 13

The Great House of Silba in the Realm of Fairhdel

With only Caraine, the caravan made better time as it wove up the mountain road towards Sildeir. The twelve round towers of House Silba, one of the oldest great houses in Fairdhel, dominated the skyline. As the party continued up the hill, Alana could make out the amber-colored granite stone walls which connected each tower. Thin, arched windows are scattered across the walls in a seemingly random pattern, along with overhanging battlements for archers. Though this stronghold had been once made for conflict, it was softened by centuries of ivy and climbing flowers which scaled the walls. Below, the walled village was protected by a massive portcullis and sharp-eyed soldiers. Sildeir was a larger city than Eyredeir and the good roads between it and the Guild house at Olentir and the port city of Dundir. Sildeir’s mines brought out some of the purest ore in the Seven Realms. Though the city was named for silver, there were also nearby mines containing copper and iron. Carts, boxes, tents and various trade goods were stacked and packed outside the village walls, ready to be sold.

They passed through the heavy iron gate where the sentries gave them wide smiles and bowed at Byronia and Alana.

A boy was sent with a message to the Great House. Inside the walls, stablekeepers hurried to take the horses. The gardens were alive with red and gold blossoms. Byronia scanned the garden, but she kept smoothing her travel clothing and adjusting her scabbards. “We should go in immediately.” She bit her lip. “If you think that’s right.”

“Orla is your sister. I’ll follow your lead.”

The carved wooden doors of the inner keep opened into the Great Hall. Stepping past the stone statues which supported the great loadstone. The first generation of House Silba had been carved in stone, but, past the statues, the Great Hall was set up in the standard Fairsinge way. Alana was transported to the time in which she and Corwin visited House Silba together to announce her pregnancy and discuss in which House the child would be named. So many years ago, but very little had changed except the latest generation of freshly painted portraits.

At the head of the hall sat Doyenne Orla upon her throne and her husband sat beside her. Alana had known she had at least one child, but the girl was young, still in the nursery. Lady Falka wore the simple robes of a priestess as was her station. The fourth born, Aldran, smiled at them in a way that made it hard to read what he was thinking. He was a fair young man. Hopefully, he would make a loyal husband someday. Perhaps due to Corwin’s urging a match had been made already.

Orla stood in her heavy blue vel

vets that matched her deep blue eyes. “Lady Alana of House Eyreid, I bid you welcome, and thank you for your service to our people. Sister, I am gladdened you have returned.”

Byronia curtsied at her sister. Alana did not as she had no need to. Caraine knelt.

“It was my pleasure, but I need to get back to my apprentices,” Alana said.

“Wait,” Orla called. “We must ask more of you …”

Alana already could see what the Doyenne was thinking. More rescues. The Doyenne motioned her herald, who scurried from the room.

He returned with a lanky man that resembled Kian who practically swept the floor with his bows.

“Fol Baker made a petition when his wife and sons were stolen.”

“I have news.” Alana quickly filled the hall with the story about how she had found Eohan alive on a slave ship, how Aedell had already died, and how she sought for his young brother and found him. (She did not speak of Kian’s shames or the Regicide and assumed she would not be asked as Orla obviously had other things on her mind.)

“Our citizens have taken refuge in Eyredeir, but there is no need when they might return home,” Orla said. “And then this child might be reunited with her mother.”

“Send an ambassador to my sister with an escort for the citizenry’s safe journey of. I protect our people; I don’t tell them where to live,” Alana said.

“I have. There has been no answer. We could hold you until we receive one,” Orla said.

Byronia’s eyes opened wider. The older lady did not believe the younger had led her into a trap and ultimately it didn’t matter. Orla was Doyenne and young people are often so stupidly headstrong in how they see the world.

“I don’t believe that you would make threats against an ancient ally,” Alana said.

“I’m not threatening you, but we must have our citizens returned to us. They are important to Sildeir.”

“Not important enough for you to fight slavers, just important enough for you to fight your allies.”

“Wait …”

Alana turned to go and looked down at the girl still on her knees.

As she suspected, she was quickly arrested and taken to a guest room. Four mice squeaked when the door opened, and they ran in all directions, seeking to crawl through a hole in the wall.

So the slavers -- or something -- are draining House Silba’s wealth. No wonder Orla would gamble so much to save those lost. No wonder Orla ordered her sister to wander.

She asked her guard, “Since I’m here at the Doyenne’s convenience, might I be bathed, and my clothes laundered?”

As she suspected, her needs were promptly met.

*

Once night fell, Alana slipped from her window and climbed the tower with the hope that the House was generally maintained, the way it had been when she and Corwin were lovers.

She reached the roof, slid through a tight opening, and climbed upon a joist. Rodents scurried past her, their tiny claws clattering on the attic floorboards. She crossed the timber without fail. She scrambled down the other side of the tower and entered the Great Hall’s roof space the same way. Below, servants were cleaning, their children were playing with a large, brown spotted atair whose floppy ears bounced as it’s six legs padded around them. Atairs always faithful pets and patient guardians of children, the animal glanced roofwards a few times and howled. Alana held her breath, but no one bothered to look up. She quickly crossed the joists to the kitchen.

Staying close to the wall, she silently slipped through the corridor and down the stairs to the visiting commoner’s quarters: a large room filled with pallets.

Alana crept in the darkness careful not to make too much noise until she saw the familiar frame of poor Caraine slumped on her pallet weeping into her hands.

Alana kneeled before her. “Don’t cry. I’m taking you to your mother.”

The girl’s voice was too loud as she sobbed. “But the Doyenne said ….”

Alana thought a curse but did not speak it in front of the girl.

The baker coughed behind her and whispered, “If you’re taking Caraine to her mother, would you take me to my sons? I heard of your battles. I’ve never fought, but I’ll keep an eye on the girl and make myself useful. I’m a good cook.”

Caraine started shivering. “But Baker what if … they find us …”

“Did anyone lay a hand on this child?”

“I’m not telling you, lest they lose it. But I haven’t -- and won’t -- lay a hand on her. I don’t blame her for what happened. I blame them,” he hissed and gathered the girl into her blankets. “Now, listen to milady.”

Caraine took Alana’s hand.

No one stopped them as they left the common visitor’s hall to the Chapel of the Thirteen. They crossed the garden to the stable, where a sleepy stableboy prepared Talia. She hoped he would be smart enough in the morning to not be chastised.

Escaping was easier than it should have been. That worried her, but there was nothing to be done about it. Behind her, Caraine leaned into her back and began to softly snore. Before the girl fell, Alana tied a spare cloak around her. Fol Baker jogged beside. Good to his word, he kept up with Talia as best as he could without complaint until they crossed the plain to the seaport, Dundir.

As the suns rose into the sky, Alana found no Guild ships but saw a long grain ship. An errand boy ran to and fro, and the captain, a Fairsinge woman, stood beside a painted sign that read PASSAGES AND MESSAGES TO SANDIER, MARDIER, EYREDEIR AVAILABLE. The crew, both Daosithian and Fairsinge, wore thin, threadbare tunics and trousers that looked like they hadn’t been washed in a fortnight. As they approached, though the crew looked thin, the ship was in good condition.

“Let’s see about that one,” Alana said.

The symmetrical shaped-hull were protected by wales and featured wing-like projections and a large housing to shelter the rudder system. Between the starboard and port posts were the folded glass hull for InterRealm travel, but other than a small cabin situated at the stern with a place for the steersman, the decking was exposed to the three suns.

“Excuse me, Captain; do you have any passage below deck? And stables for my horse?” Alana asked.

She licked her flaking lips. “I keep a single fine cabin and stables, but it’d be fifty sovereigns.”

“I’ll pay forty now, and if my horse is in good health when we arrive, you will get an additional twenty.”

“Let me see the money.”

Alana showed the captain the money along with her Martlet broach. The captain grunted and called, “Gavon.”

A too-skinny boy of nine raced down the gangplank. His bare feet slapping against the weathered wood.

They were led past men hauling bags of grain up the wide gangplank.

As they crossed the deck, Alana witnessed too-slender parents giving crusts of bread to their too-slender children. Their eyes followed her as they followed Gavon through the hatch.

“Stay close to me, I wouldn’t half-surprised if we were robbed.”

“If the Martlets really wandered, the elfkin wouldn’t suffer,” Fol muttered.

Talia was stabled in a dirty looking stable beside a brace of birds and a drift of hogs. She snorted, obviously unhappy.

Gavon led them to a small, dank room. It’s only separation from the rest of the ship was a red curtain. Other than the chamberpot in the corner, its only asset was they would remain below deck.

“The captain will be having a laugh with his purser,” Alana said looking around at the bare room.

Gavon returned carrying three hammocks.

A youngish woman, who resembled Gavon, followed with a musty log book. Her loose tunic threatened to fall off her narrow shoulders as she bowed. “Cap said, forty now, twenty ashore?”

Alana inclined her head at her and handed her the forty.

She plopped onto the deck and counted it slowly while Gavon quickly ran the hammock ropes around her. Once satisfied, the purser wrote Roark out a receipt. “Ma

ny thanks, milady, ...”

“Alana, the thirty-seventh Martlet of House Eyreid.”

“I suppose you’ll be wanting all the comfort this ship will give?”

Gavon opened his mouth wide and tugged at her wrist.

Alana took a step back. “Purser, I, my friends and I only wish for transport.” She took a package of smoked rabbit and handed it to her. “Eat here, so it isn’t taken from you.”

The purser took the meat, sat down on the deck and tore it into two uneven halves. As Alana expected she would, she gave Gavon the bigger piece, before devouring hers in seconds.

Orders echoed through the ship. The purser grabbed the ship’s log and purse in one hand and Gavon by the other. They raced out. Once the sailors were out of earshot, Alana smiled at the others. “Perhaps some lanolin would be in order?”

“That’d be good.” Fol nodded.

A commotion was heard above them. Hoofbeats. She heard Gavon, but no other. Byronia. Still, there was nothing to be done. She tucked Caraine into a hammock furthest from the door. Fol sat below the hammock and held the girl’s hand.

Byronia entered the room, her hands in clear view. “You might have told me we were leaving; I almost missed our transport.”

Alana made no move for her weaponry as Gavon brought in another hammock and strung it up. Once the boy was gone, she said, “I’m returning this child to her mother.”

“We know. Orla said you were a very bad example. So I said, ‘Orla, you told me to be a Martlet. A Martlet wanders for the good of our people. Alana just wants to reunite these families.’ And took my leave.”

“With permission?”

Byronia’s deep blue eyes, which mirrored the Fairsinge sea outside the porthole, held wretchedness. “Orla knows I went after you, but I need not permission to fulfill my vows.” Still, the young Martlet walked over to Caraine’s hammock. “You’ve suffered enough for several lifetimes. By my life or death, I shall find your mother and bring you to her. You and she can see to your future; it is not mine to dictate. I wander for the good of my people.”

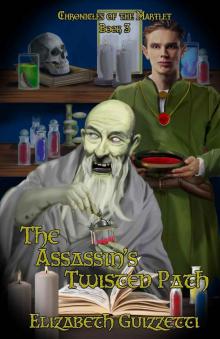

The Assassin's Twisted Path

The Assassin's Twisted Path The Morality of A Necromancer

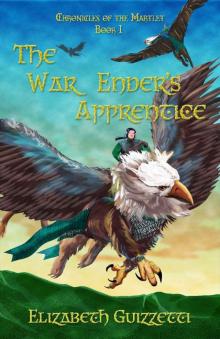

The Morality of A Necromancer The War Enders Apprentice (Chronicles of the Martlet Book 1)

The War Enders Apprentice (Chronicles of the Martlet Book 1)